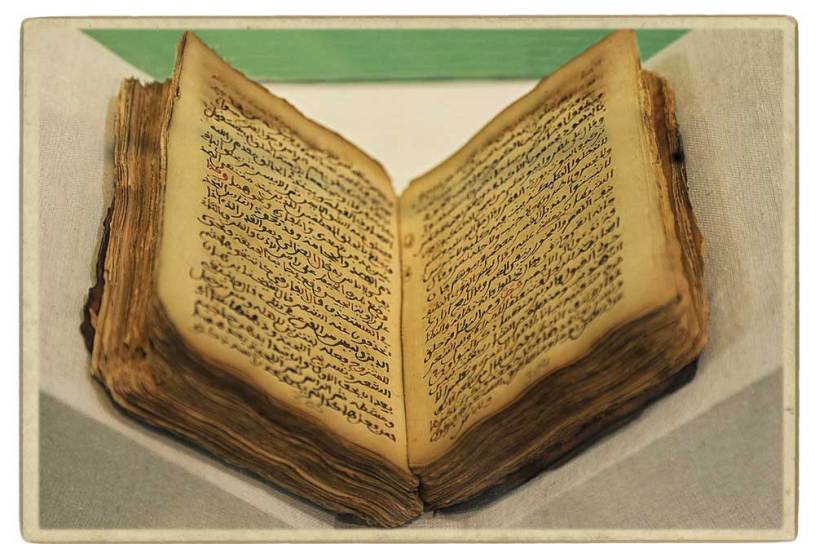

The intellectual colonization of the Muslim world is a tale of gradual erosion and subtle subversion. Long before the ideological turmoil of the 1960s, colonial powers systematically dismantled traditional Islamic education systems, replacing them with Western-style institutions. This deliberate strategy aimed to erode the intellectual foundations of Islamic societies, ensuring the dominance of colonial rule. Esteemed centers of learning, such as Al-Azhar in Egypt, faced immense pressure to conform to new educational paradigms, stripping away centuries of rich scholarly tradition. As the 20th century progressed, the Muslim world found itself caught in a whirlwind of conflicting ideologies and socio-political upheavals, setting the stage for a profound transformation.

The 1960s: A Decade of Ideological Infiltration

The 1960s marked a pivotal era in the intellectual landscape of the Muslim world. During this decade, a myriad of ideologies—Marxism, communism, secularism, capitalism, and liberalism—began to infiltrate and further erode the cultural and Islamic heritage that had been preserved for centuries. These ideologies were introduced with the intention of undermining Islamic intellectual autonomy and devaluing its worth.

These external influences created a cacophony of conflicting ideologies, each vying for dominance within the Muslim world. The traditional Islamic intellectual framework, which had been the bedrock of Muslim societies, was increasingly marginalized. The infiltration of these ideologies resulted in a profound crisis of identity and purpose among Muslims, who struggled to reconcile their heritage with the new intellectual currents.

The 1970s: Turmoil and Transformation

As the Muslim world grappled with these external influences, the 1970s emerged as a crucial period. This decade was characterized by numerous wars and conflicts, including the Yom Kippur War of 1973 and the Lebanese Civil War, which began in 1975. These conflicts exacerbated the instability in the region, further undermining the intellectual and cultural foundations of Muslim societies.

Concurrently, the Gulf countries experienced an unprecedented economic boom due to the sharp rise in oil prices following the 1973 oil embargo. This newfound wealth facilitated the spread of the Wahhabi ideology, which had its roots in Saudi Arabia.

Amidst all the instability and ideological chaos, Wahhabism found incredibly fertile ground due to its anti-intellectual worldview. This perspective was not only antagonistic towards Western ideas but also targeted the rich Islamic tradition itself. Wahhabism, buoyed by considerable financial backing, began to exert a profound influence across the Muslim world. This ideology was notoriously hostile to academic social knowledge and criticism. It dismissed classical intellectual orientations and deductive reasoning, branding them as corrupt practices. Intellectual traditions such as Ash’arism, Maturidism, and the entire juristic tradition were deemed heretical under this new ideological framework. This approach dealt a crucial blow to Muslims worldwide, undermining the rich intellectual heritage that had characterized Islamic civilization for centuries.

The Rise of Wahhabism: 1980s and 1990s

In place of these diverse intellectual traditions, Wahhabism usurped the concept of Ahl al-Sunnah wa al-Jama’a, a term used by Sunni Muslims. This exclusivist ideology, instead used for themselves, to establish a singular interpretation of Islam, marginalizing all other schools of thought and interpretations.

By the 1990s, the dominance of Wahhabism in the Muslim world had become almost unassailable, thanks in large part to its substantial financial resources. The oil wealth of the Gulf countries enabled the widespread dissemination of Wahhabi teachings through the funding of mosques, schools, and media outlets. This concerted effort to propagate Wahhabi ideology resulted in a significant shift in the intellectual and religious discourse within the Muslim community.

The Impact of Contemporary Salafism

Salafi movements, particularly the bonding of Wahhabism and Salafis has successfully taken root in the contemporary Muslim world, producing a trend anchored in feelings of defeatism, alienation, and frustration. This ideology is neither linked with modern institutions nor the Islamic heritage. Unlike traditional schools of thought, Salafism is characterized by a broad range of ideological tendencies but is consistently supremacist, compensating for defeatism and disempowerment with self-righteous arrogance against the “other”—whether Westerners, non-believers, or even fellow Muslims.

Salafis exaggerate the role of religious texts and minimize the interpretive role of humans, using texts as a shield against criticism. Their approach is often authoritarian, using religious doctrine to assert power and silence opposition, particularly against subjects like human rights or aesthetics, which they erroneously dismiss as Western inventions. This Salafi worldview leads to a reactionary stance that rejects modernity while ironically adopting Western philosophical paradigms without any Muslim input.

Interests such as protecting society from perceived moral threats are empirically verified, while moral or ethical values are disregarded. This leads Salafis to ignore the rich humanistic legacy of Islamic civilization, which includes contributions to philosophy, arts, and ethics. Instead, they claim Islamic successes of the past while denouncing modern achievements, fostering a mix of arrogance and humiliation.

Militant Salafi groups, like al-Qaeda or the Taliban, reflect extreme manifestations of these ideological currents. Though sociologically marginal, their symbolic acts of power compensate for disempowerment and reflect a reaction to despotic governments and foreign interventions. Historically, extremism in Islam has been marginalized by traditional institutions, but the modern lack of these institutions allows extremist ideologies to flourish unchecked.

The problem today is that traditional Islamic institutions that once marginalized extremism no longer exist. This absence makes contemporary Salafi orientations more threatening to the integrity of Islamic values than previous movements. For the first time in history, the spiritual centers of Mecca and Medina are under prolonged control of a Wahhabi-Salafi state, posing a significant challenge to the rich intellectual and ethical traditions of Islam.