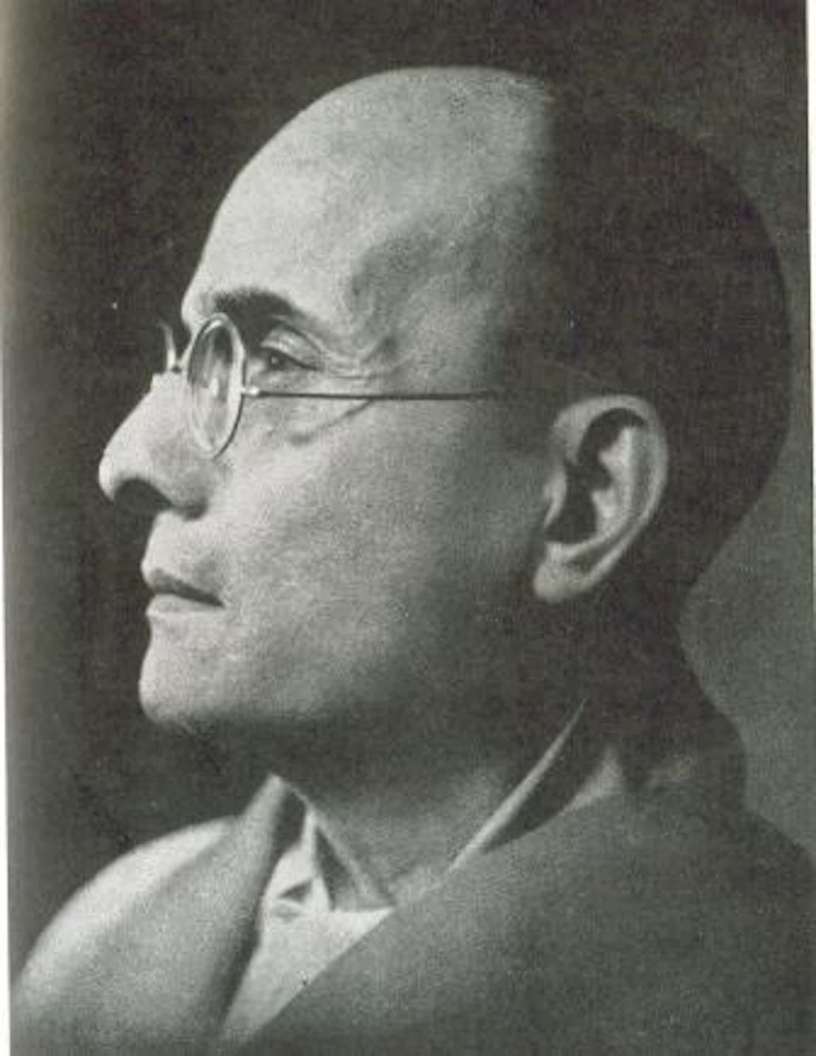

In the tumultuous political and cultural landscape of early 20th-century India, one figure stood out for his radical reimagining of Indian identity—Vinayak Damodar Savarkar. Known as the chief architect of Hindutva, Savarkar’s ideology sought to redefine Indian nationalism by centering it around a Hindu cultural and religious identity. Central to his philosophy was a historical narrative that cast Muslims as foreign aggressors who disrupted the nation’s social and cultural harmony. For many, these views continue to shape political discourse in contemporary India. But how accurate are Savarkar’s historical interpretations? Were his views on Muslims rooted in objective history, or were they exaggerated to serve an ideological agenda? This article delves into the complex, often contentious, historical perspectives of V.D. Savarkar and their implications today.

Savarkar’s View of Muslim Rule: The Image of Oppression

One of Savarkar’s most persistent themes was the depiction of Muslim rule in India as an era of unrelenting oppression. He focused heavily on the invasions and conquests by figures like Mahmud of Ghazni, the Delhi Sultans, and Mughal emperors like Aurangzeb, portraying these rulers as foreign aggressors bent on subjugating the Hindu population. He argued that these rulers not only plundered Hindu temples but also sought to impose Islamic culture, often through forced conversions.

While there is no denying that there were moments of violence, destruction, and coercion, many historians argue that Savarkar’s portrayal is exaggerated. The actions of rulers like Mahmud of Ghazni, who indeed sacked temples like Somnath, were more likely motivated by political and economic gains than religious zealotry. Furthermore, the depiction of Muslim rulers as uniformly hostile overlooks figures like Akbar the Great, who promoted religious tolerance and actively integrated Hindus into his administration. Savarkar’s portrayal of Muslim rule as a monolithic period of oppression ignores the complexities of governance, where alliances between Hindu and Muslim rulers were often formed, and cultural exchange flourished.

The Issue of Forced Conversions: Exaggerated or Grounded in History?

Another significant point in Savarkar’s interpretation of history is the emphasis on forced conversions to Islam. According to Savarkar, Muslim rulers sought to expand Islam through coercion, presenting Islam as a threat to the survival of Hinduism in India.

Historical records, however, suggest a more nuanced picture. While there were cases of forced conversions, they were not as widespread or systematic as Savarkar claimed. Many conversions occurred for socio-economic reasons or due to the influence of Sufi saints, whose spiritual teachings appealed to lower-caste Hindus seeking social mobility. Sufi missionaries, far from coercing individuals, often emphasized inclusivity and the universality of God, attracting followers across religious boundaries.

Additionally, intermarriage, trade relations, and pragmatic conversions for social advancement contributed to the spread of Islam in India. The voluntary nature of many of these conversions challenges Savarkar’s narrative, which tends to ignore the spiritual and social appeal of Islam for many Indians.

The Destruction of Temples: A One-Dimensional Narrative

One of the most powerful symbols in Savarkar’s historical narrative is the destruction of Hindu temples by Muslim rulers, which he portrayed as deliberate acts to erase Hindu culture. While some temples were indeed destroyed, historians have argued that these actions were often motivated by political and economic factors, rather than purely religious animosity. Temples were centers of wealth and political power, and attacking them could weaken rival states.

Savarkar’s narrative overlooks the complex realities of the time, where many Muslim rulers patronized Hindu temples and showed respect for local religious customs. For example, Mughal rulers like Akbar and even some sultans of the Deccan had Hindu officials in their courts and offered patronage to Hindu temples. These examples of cultural exchange and tolerance paint a more complicated picture than Savarkar’s straightforward narrative of destruction and domination.

Muslims as Foreign Invaders: A Historical Inaccuracy?

Perhaps the most pervasive element of Savarkar’s historical interpretation is his view of Muslims as foreign invaders who never fully integrated into Indian society. In his eyes, Muslims were outsiders who disrupted the cultural and social fabric of India, maintaining loyalties to a religion and civilization that originated outside the subcontinent.

This view, however, is deeply flawed when applied to the historical reality of Indian Muslims. By the time Savarkar was writing, Muslims had been living in India for centuries, and many were descendants of indigenous converts rather than foreign invaders. Furthermore, Islamic culture in India had evolved into something uniquely Indian, with its own distinct language (Urdu), art, architecture, and cuisine. The idea that Muslims were a foreign presence ignores the deep integration of Islamic culture into Indian society and the fact that many Muslims considered India their homeland just as much as Hindus did.

A Monolithic View of Muslim Rule: Ignoring Diversity and Collaboration

Savarkar’s portrayal of Muslim rule as a monolithic period of oppression overlooks the regional diversity and variation in Muslim governance. Different dynasties and rulers had different policies, and many Muslim rulers collaborated with Hindu elites and adopted policies of religious tolerance and cultural syncretism.

For example, the Mughal Empire, especially under Akbar, promoted a policy of Sulh-e-Kul (peace for all), where different religions were allowed to coexist peacefully. Many Hindu warriors, administrators, and scholars held key positions in Muslim courts, and the arts and architecture of the time reflect a fusion of Hindu and Muslim traditions. The mutual influence between these two communities challenges the simplistic narrative of constant hostility.

The Legacy of Savarkar’s Views and Their Impact Today

Savarkar’s interpretation of history, particularly his views on Muslims, continue to have a significant impact on modern Indian politics and society. His philosophy of Hindutva, with its emphasis on Hindu cultural dominance, has been embraced by Hindu nationalist groups and political parties, particularly the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). These groups have used Savarkar’s historical narrative to justify policies and rhetoric that often marginalize Muslims, casting them as outsiders or a threat to national unity.

The implications of this historical revisionism are stark. Communal tensions between Hindus and Muslims have been exacerbated, with incidents of mob violence, lynchings, and discrimination against Muslims rising in recent years. Policies like the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), which critics argue discriminates against Muslim refugees, can be seen as a continuation of the exclusionary ideas Savarkar espoused.

Conclusion: A Call for Historical Balance

In conclusion, while Savarkar’s views on Muslims are rooted in certain historical facts, they are often selective, exaggerated, and one-sided. His portrayal of Muslim rule as uniformly oppressive, focused on forced conversions and temple destruction, ignores the more nuanced, complex reality of Hindu-Muslim relations in India’s past. History shows that periods of conflict were often followed by periods of collaboration and cultural exchange, and that Muslims were not simply foreign invaders but integral parts of Indian society.

As India continues to grapple with issues of identity, nationalism, and pluralism, it is essential to approach history with a balanced, nuanced perspective. Acknowledging both the conflicts and the cooperation between Hindus and Muslims can foster a more inclusive vision of the nation’s past—and its future.