“Do not consume one another’s wealth unjustly or send it to the rulers in order that you to consume a portion of the wealth of others while you know [it is unlawful].”

— Surah Al-Baqarah (2:188)

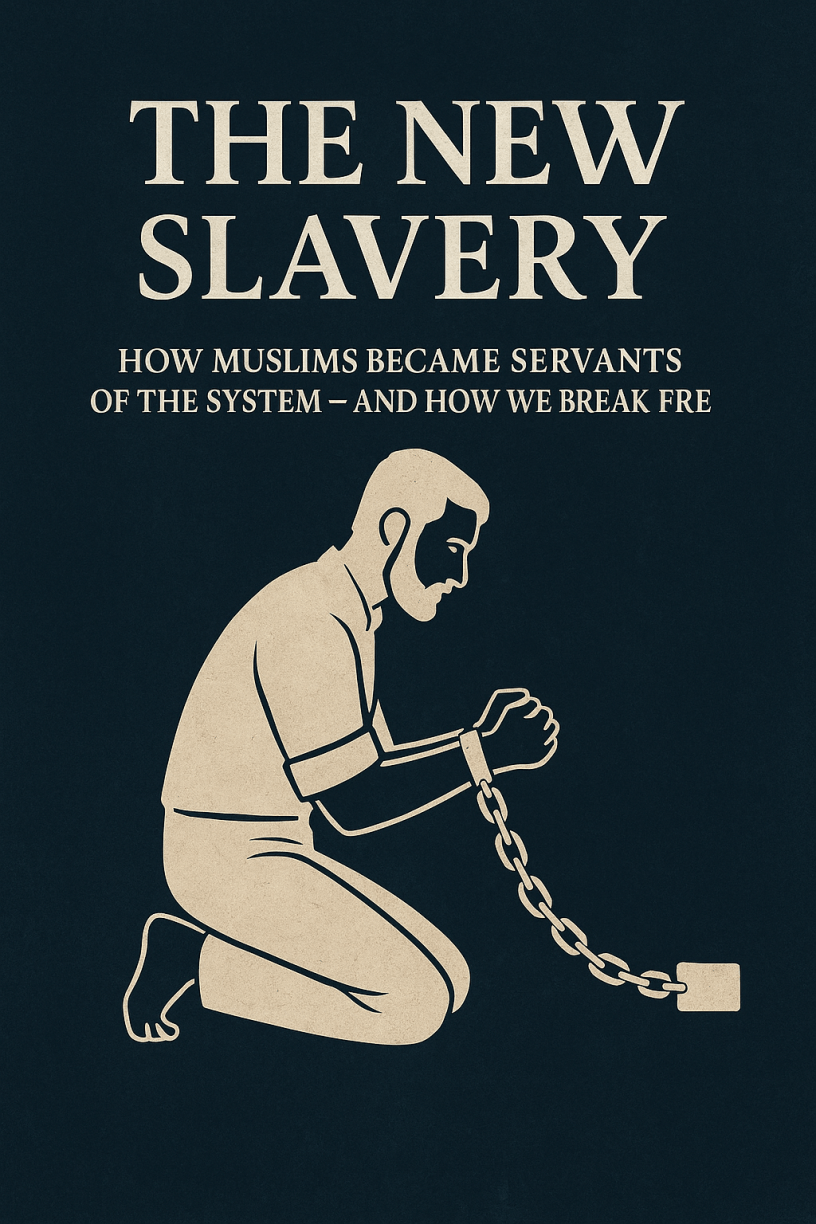

What if we told you that 80 to 90 percent of Muslims today live in a state of modern-day slavery — not through shackles or chains, but through contracts, corporations, and consumerism? This isn’t hyperbole. When compared to the premodern Islamic world, where perhaps only 5 to 15 percent of the population lived in any kind of servitude, today’s reality is stark. The average Muslim in the modern world is more educated, more urban, and yet more economically dependent, spiritually stifled, and systemically trapped than at any other point in our history.

What Was Slavery in Islam?

In the Islamic tradition, slavery was not based on race or the idea of permanent subjugation. It existed as a transitional institution — a reality of the time, but one that Islam sought to humanize, regulate, and eventually dissolve. A slave in Islam had the right to enter into a contract of emancipation, known as mukataba, allowing them to work and earn their freedom. Slaves had rights to food, clothing, humane treatment, and rest. It was strongly encouraged to free them, either through personal virtue or via zakat.

Moreover, Islamic history is filled with examples of former slaves rising to positions of influence — scholars, generals, and rulers who began their lives in servitude but were elevated through the principles of dignity, justice, and opportunity embedded in Islam. The ultimate goal of the Islamic economic ethic was not to preserve slavery, but to create a society where it would no longer exist — replaced by brotherhood, equity, and shared prosperity.

Modern Slavery: The Corporate Kind

You might think that having a job, a salary, and a boss is just a normal part of life — a sign that you’re responsible, productive, and living a decent life. And yes, there is dignity in honest work. But we must pause and ask: is this system truly as normal or harmless as it seems?

What if the model we’ve all accepted — waking up to work for someone else, just to survive — is actually uncomfortably close to the slavery our religion sought to eliminate? Not slavery with chains, but slavery through dependency. You don’t own your time. You don’t own the product of your labor. You cannot walk away freely without risking your livelihood. In fact, if we were to define a ‘slave’ in Islamic terms — someone whose time, output, and mobility are controlled by another — then this condition, although modernized and polished, fits uncomfortably well. You’re told you are free, but the structure of your daily life is dominated by forces you do not control, in service of people you do not choose. Most of your life is locked into serving a system that gives you just enough to live, but never enough to be truly independent. This is not the dignified economic life that Islam envisioned for the believer.

In today’s system, the more you work, the more stress, and fragility you inherit. You may technically be free, but functionally, you are disposable. Replaceable. Measured not by your inherent worth, but by your economic output. This modern form of servitude has no built-in path to dignity — only the illusion of choice and freedom.

This modern form of slavery wears a suit, speaks in HR language, and gives you weekends off — but the underlying dynamic remains: your energy fuels someone else’s empire. Your labor builds wealth for corporations or elites who care nothing for your future. And when you’re no longer profitable, you’re cut loose.

It’s a system that has trained Muslims — once the freest of peoples — to become obedient servants of the marketplace. This is not the freedom Allah intended for us. This is not the life of dignity promised by the Sunnah.

And perhaps the greatest tragedy is that most modern Muslims can no longer envision what a truly free Muslim looks like. A free Muslim is not one who merely consumes halal products or dresses in modest fashion while working for unjust systems. A free Muslim is someone who owns their time, who earns with their own hands, who has space to think, worship, and contribute without fear of financial ruin. A free Muslim is someone who lives with purpose, gives with sincerity, and walks through life knowing they serve no master but Allah.

And let us be clear — this is not meant to make anyone feel ashamed of their current circumstance. Rather, it is meant to awaken something deeper: an awareness that can open doors, shift mindsets, and reorient lives. If we don’t name the problem, we can’t begin to fix it. Without knowledge, there can be no clarity. Without clarity, there can be no direction. And without direction, the Ummah remains lost.

The Global Machine Feeds on This

The world economy today is structured to thrive on wage-slavery. Corporations outsource their labor to the Global South — often to Muslim-majority countries — because it’s cheaper to exploit people there than to pay fair wages elsewhere. Muslims in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Egypt, Morocco, and beyond stitch clothes, assemble electronics, and process goods that they will never afford, for wages that barely feed them.

Meanwhile, elites in these same countries serve as willing middlemen. They underpay their own people, hoard access to resources, and secure contracts with foreign firms that drain wealth from the community. In this way, global capitalism has found its perfect mechanism: exploit the poor through the rich who look like them.

Brands that Muslims consume daily — fast fashion, smartphones, even some halal food franchises — are built on the backs of this labor. The irony is painful. The Ummah has become the engine of its own economic servitude.

The Bitter Truth: Muslims Are Enslaving Muslims

Here lies the hardest truth to face: it is no longer just foreign powers who exploit Muslim labor. It is Muslims themselves. The factory owner who underpays his workers. The land baron who keeps sharecroppers in permanent debt. The religious businessman who quotes hadith but hoards wealth. These are not fringe cases. They are systemic realities.

Many of the people benefiting from modern slavery wear Islamic clothing, frequent mosques, and donate to charity. Yet they perpetuate a system that grinds down their fellow Muslims into economic dust. The Ummah, instead of lifting itself up together, has become fragmented — with some using Islam as a shield while living off the backs of the rest.

We wear garments sewn in sweatshops, live in homes built by underpaid migrant workers, and eat food harvested by people working in dehumanizing conditions. And then we gather in comfort and wonder: why is the Ummah weak?

A Hypothetical Path Forward: What This Could Look Like in Practice

Let’s imagine a small town in a Muslim-majority country. It is filled with unemployed youth, underpaid tradesmen, and a handful of local shopkeepers. A few community members come together, not to build another mosque or school — but to start a micro-waqf.

They raise $10,000 — not from one wealthy donor, but from 200 people giving $50 each. With this, they buy basic tools and rent a shared workshop space. They choose to focus on carpentry, tailoring, and electrical repair — trades already present but under-supported.

They organize a rotating apprenticeship program. Young men and women are trained by older tradesmen, with a small stipend supported by the waqf. The products they make — furniture, clothing, repair services — are sold locally and through an online marketplace built by a few volunteers in the diaspora.

Profits are reinvested into buying better tools, expanding services, and launching new trades — such as plumbing or food processing. Everyone working in the system gets a share, and no one is paid unjustly. Over time, a small network of ethical, spiritually grounded, and economically self-reliant businesses emerges.

Now imagine this model replicated in 50 towns across the Muslim world, each networked and supported by Muslims abroad who are tired of charity that doesn’t empower. This is not without precedent. In the Ottoman era, the Ahi brotherhoods functioned as Islamic trade guilds that trained craftsmen, regulated ethics in commerce, provided spiritual development, and ensured mutual financial support — all grounded in Islamic values. Every member had a say, every apprentice had a mentor, and every transaction was a form of service to Allah.

Even today, worker cooperatives, microfinance networks, and social enterprises in places like Indonesia, Turkey, and parts of Africa echo similar principles — local ownership, profit-sharing, and communal reinvestment. The key is to adapt these frameworks to modern tools and technologies while preserving their Islamic soul.

It starts small, but grows with each generation — especially when rooted in trust, shared risk, and a vision for collective liberation.

This is not utopia. It’s a model — a vision of what’s possible when we combine knowledge with action, skills with structure, and faith with finance.

Muslims living in the West are uniquely positioned to fund, support, and even help initiate these models. With access to capital, technology, and legal freedoms, they can redirect resources to empower their brothers and sisters abroad — not through charity, but through equity, partnership, and shared purpose. The diaspora must stop sending money to feed dependency and start investing in structures that restore dignity.

There is a path forward — but it requires the courage to break from comfort and imitation. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) built a society rooted in economic dignity. His model was not charity-driven consumerism, but a system where people were empowered through their own work, where business was ethical, and where wealth was a trust to be shared, not hoarded.

He also elevated skilled labor. He endorsed partnerships in which risk was shared and profits were fair. He established zakat and waqf as tools for economic redistribution and social empowerment. Guilds, or isnaf (ethical trade collectives), flourished across the Islamic world, creating networks of craftspeople who supported each other and upheld ethical standards.

Crucially, the scholars of his time and generations after played a central role in shaping this vision. They taught economic ethics, held rulers and merchants accountable, and ensured that trade was not just lawful but spiritually uplifting. Their presence in marketplaces was not incidental — it was intentional, to safeguard justice and prevent exploitation. In reviving our economic dignity, scholars must again take their place — not merely as jurists in ivory towers, but as ethical guardians within the lifeblood of the economy.

To revive the economic Sunnah, we must begin by training Muslims in essential trades — carpentry, plumbing, tailoring, electrical work, farming, and beyond. However, we must be clear: simply having skills will not liberate us if the economic system remains exploitative. In a system where labor is undervalued and controlled by elites, even skilled workers remain dependent, underpaid and trapped.

Therefore, training must be coupled with structural transformation. These skills must be protected and empowered through ownership — shared tools, cooperative workshops, and community-based micro-enterprises. We must reject the model where a skilled worker becomes merely a better-paid servant. Instead, the goal is to turn skilled individuals into partners, producers, and eventually owners within ethical, barakah-centered economic models.

To do this, we must rebuild the support structures Islam once gave us — waqf-funded training centers, zakat-backed capital, and markets built for ethical trade rather than mass consumption. Only when we surround skill with systems of justice and cooperation can it become a tool of liberation rather than exploitation. These are not menial tasks; they are the foundation of every civilization. We must pool our resources to establish micro-waqf businesses, where capital is collectively owned and profits are reinvested into the community. We must build ethical markets — online and offline — that value barakah over margin.

We must stop measuring our success by the ability to get a job in someone else’s system, and instead build systems of our own — rooted in Qur’an, Sunnah, and centuries of wisdom.

Yes, it’s a tough sell. But so was Islam in the beginning. And like those before us who faced mockery, resistance, and fear — we too are called to rise. Not with slogans. But with tools, trade, trust, and tawakkul.

Because until we stop living like slaves, we will never think like believers.

Imagine a generation of Muslims who no longer ask permission to survive. Who own their tools, their time, and their trade. Who live lightly but think freely. Who work not to serve masters, but to serve Allah. That generation begins with us.