Cervantes’ Don Quixote is usually described as the world’s first European modern novel, a brilliant parody of knightly romances. But the book is more than satire. Beneath its humor lies a lament: the death of chivalry in Spain. What is rarely acknowledged, however, is that chivalry was never truly European. It was borrowed — drawn from the Islamic tradition of futuwwa — and later hollowed out. In Islam, chivalry grew from its own soil, rooted in the Qur’an and the Prophet’s, peace be upon him, example. In Europe, it was a foreign graft, ultimately abandoned and romanticized into mere gallantry toward women.

Chivalry’s Roots in Islam

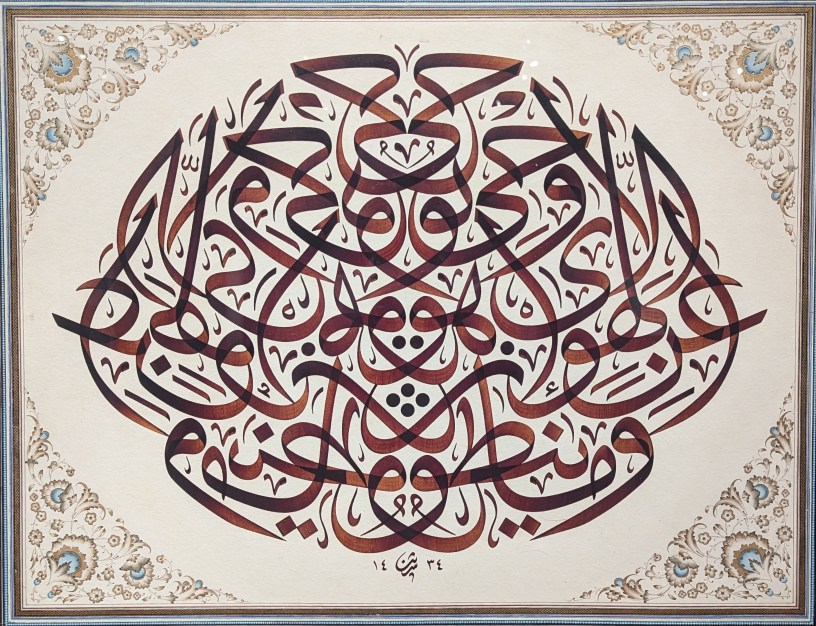

The ethic of chivalry was first written down in the Muslim world. As early as the ninth century, the great writer al-Jāḥiẓ (d. 868) of Baghdad composed a treatise on futuwwa — Islamic spiritual knighthood. Though that text is lost, later sources confirm its existence.

A century later, Abū ʿAbd al-Raḥmān al-Sulamī (d. 1021) of Nishapur composed Kitāb al-Futuwwa, the earliest surviving manual. In it, he described the virtues of the true knight: generosity, humility, loyalty, protection of the weak, and service to God. Tosun Bayrak’s English translation (The Book of Sufi Chivalry: Kitab al-Futuwwah, Inner Traditions, 1983) remains the clearest window into this tradition.

Futuwwa was more than battlefield conduct. It was a code of humane warfare, urban brotherhood, and spiritual discipline. To be a fatā was not simply to fight bravely; it was to embody restraint and mercy, to live honorably among others, and to see dignity in one’s enemy.

Mallorca: The Borrowed Ideal

Fast-forward to 13th-century Mallorca. Recently conquered from Muslims (1229), the island still carried the intellectual and cultural memory of Islam. Here, Ramon Llull (1232–1316) wrote The Book of the Order of Chivalry (1274), considered the first systematic European treatise on knighthood (trans. Noël Fallows, 2010).

Llull, who studied Arabic and engaged deeply with Islamic thought, defined the knight as defender of the weak, servant of God, humble, generous, and just in war. His work mirrors al-Sulamī’s manual so closely that the parallels are unmistakable. The first European codification of chivalry was written in a place steeped in Islam’s legacy, echoing an ethic Europe did not originate but borrowed.

From Knight to Conquistador

But Europe’s relationship to chivalry was shallow. Once the Reconquista ended, Spain no longer needed ideals of restraint. Humane warfare was discarded in favor of religious uniformity and imperial conquest.

- The knight, bound by a moral code, disappeared.

- The conquistador, driven by greed and forced conversions, took his place.

Forced baptisms, inquisitorial torture, and colonial massacres revealed that the ethic of honor had been swept aside (Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition, 1997). In Spain, the soil that had briefly sustained chivalry — convivencia with Muslims and Jews — was uprooted (María Rosa Menocal, The Ornament of the World, 2002).

Don Quixote: Satire with Painful Truth

This is why Cervantes’ Don Quixote (1605) is more than parody. Quixote is absurd precisely because Spain had no place for knights anymore. In the age of conquistadors, a knight errant could only be a ghost.

Sancho Panza, with his proverbs and earthy wisdom, carries echoes of Spain’s suppressed Muslim past — the folk wisdom of convivencia. Together, Quixote and Sancho form a tragic duo: the shadow of an ethic Spain abandoned, and the shadow of a world it destroyed.

Cervantes himself had lived five years enslaved in Algiers (1575–1580). Far from hating Muslims, he wrote about them with nuance, even admiration (María Antonia Garcés, Cervantes in Algiers, 2002). He had seen another world where honor still survived — and perhaps longed for what Spain had lost. After his release, he even returned to North Africa as a royal messenger — a sign that his ties to the region went deeper than captivity alone. He had seen another world where honor still survived — and perhaps longed for what Spain had lost.

The Romantic Transformation of Chivalry

After Cervantes, “chivalry” in Europe was reduced to gallantry. It was transformed into gestures of courtesy toward women, detached from its martial and ethical roots.

What had once been an ethic of restraint in war, justice for the weak, and dignity for the enemy was replaced by polite manners and romantic ideals. Meanwhile, Europe’s wars became increasingly ruthless, governed by the new principle: the stronger dictates who is worthy of humanity. Over time, this hardened into racial hierarchies: to be European was to be fully human; everyone else was expendable.

Chivalry Alive in Islam: Emir ʿAbd al-Qādir

Yet chivalry did not die. It endured in the Muslim world, where it had always been rooted. The clearest modern proof is Emir ʿAbd al-Qādir al-Jazāʾirī (1808–1883) of Algeria.

- He treated French prisoners with dignity, often sharing his own scarce food with them, even to the point of personal deprivation. When he could not provide for their needs, he released them — an act that astonished his enemies. This was not strategy but principle: in Islam, it is forbidden to hold captives if they cannot be treated humanely (Charles Henry Churchill, The Life of Abdel Kader, 1867).

- He protected Christian civilians during violence in Damascus, saving thousands of lives and earning worldwide admiration, along with gifts from leaders across the globe. Among them was a revolver sent by Abraham Lincoln, who honored him as a man of rare courage and humanity (John Kiser, Commander of the Faithful: The Life and Times of Emir Abd el-Kader, 2008).

- Even European officers admitted that he embodied an ethic they no longer possessed.

And yet, true to pattern, France betrayed him — imprisoning him despite promises of safe passage. Europe could admire chivalry when it was convenient, but never truly live by it.

The story is clear. Chivalry was not Europe’s creation. It was borrowed from Islam, codified briefly in places like Mallorca, parodied by Cervantes when it was abandoned, and then reduced to empty gallantry. In Islam, by contrast, chivalry remained alive, rooted in the Qur’an, the Sunnah, and the Sufi tradition. Figures like Emir ʿAbd al-Qādir prove that this ethic survived into modern times, long after Europe had discarded it.

Don Quixote is the obituary of European chivalry. Emir ʿAbd al-Qādir is its living proof in Islam. The legacy is undeniable: Europe’s knight became the conquistador. But the Muslim fatā — the man of chivalry — never died.